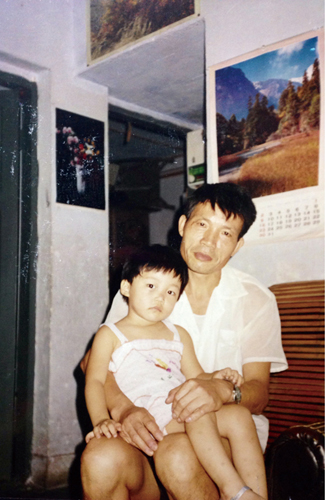

My mother’s father died when she was only 19, so my conception of a grandfather comes solely from Grandpa Chen – my dad’s dad. I didn’t properly meet him until we visited China in 1997, the summer before I turned 11. He and my grandmother had taken care of me as a baby, but I had no memories of my stay with them in Shuifu County, Yunnan.

I was a bit nervous about meeting him nearly ten years later, but Mom assured me he’d been eagerly awaiting our arrival in Kunming – and so he was. He folded my sister Nancie and I into a big bear hug and pushed us towards a dining table groaning with home-cooked dishes. When I mentioned I liked mangoes, Grandpa promptly rushed out of the house and returned with a heap of sweet, yellow fruit.

He doted on us throughout the trip, constantly checking to see whether Nancie or I needed food, water, a break, or a bathroom. He held our hands whenever he could, sat next to us at the dinner table, and listened raptly to the minutiae of our lives in Canada.

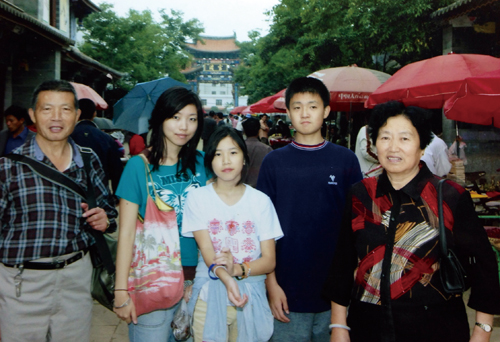

This would remain a theme throughout the years. When we moved back to China in 2002, he was as stoic as ever in his faithfulness. His questions annoyed me more as a surly teenager, but we continued to see each other and travel as a family, the high point being my parents’ 25th wedding anniversary in Hainan.

Last November, I took a week off from work to visit my grandfather in the hospital. Mom had called a few days earlier to say he wasn’t well. There was reportedly fluid in his lungs and he’d lost at least 5kg, but the doctors couldn’t find a cause. My parents wouldn’t be able to fly to Kunming until later, so I was the sole visitor that week.

I almost didn’t recognize him. My grandfather had always been a vigorous man with a crew cut and a wiry build; the man in the bed had sunken cheeks and a wan complexion, with wrists so thin they seemed likely to snap if I held them too tightly.

For a week, we settled into a routine where I arrived at the hospital in the early afternoon, we shared some fruit if he had the appetite, a nurse came by to drain the fluid from his lungs or examine him, he dozed off, and I sat by his bed and wrote or drew until he woke up again. When I wasn’t at the hospital or doing work, I took long walks through the city.

I asked Grandpa about his upbringing, which he gradually uncovered between fits of sleep. “There’s not much to tell,” he said. But there was. His father had crossed over from Sichuan as a young man and operated a successful inn and tobacco shop. That all changed with the arrival of the Cultural Revolution; the business crumbled and his brothers left to seek their fortunes. By the end of the Revolution, all four of his siblings – two older brothers and two older sisters – were gone.

He spoke matter-of-factly, without remorse or resentment. I took notes as fast as I could, prompting other visitors to ask why. How could I possibly explain that that this was the only way I knew how to deal with the situation? That I didn’t know if this would be the last time? Reluctantly, I flew back to Beijing.

About a month later, Dad called me to say that Grandpa had passed away. I felt numb upon hearing the news but crumpled into bed when I got home and proceeded to wail like an injured animal, no doubt alarming the neighbors.

Though I regret not knowing him better, our conversations in the hospital revealed much more than I thought; it turns out that my dad also wasn’t aware of my great-grandfather’s Sichuan roots. To me, the experience had underscored the urgency of talking to older generations while they’re still here.

This article originally appeared in the June 2014 issue of beijingkids. To find out where to get your free copy, email distribution@truerun.com or view it on Issuu.